We've passed the peak of the economic cycle and everyone is sleeping on it

In late 2024, economic narratives are in a paradox:

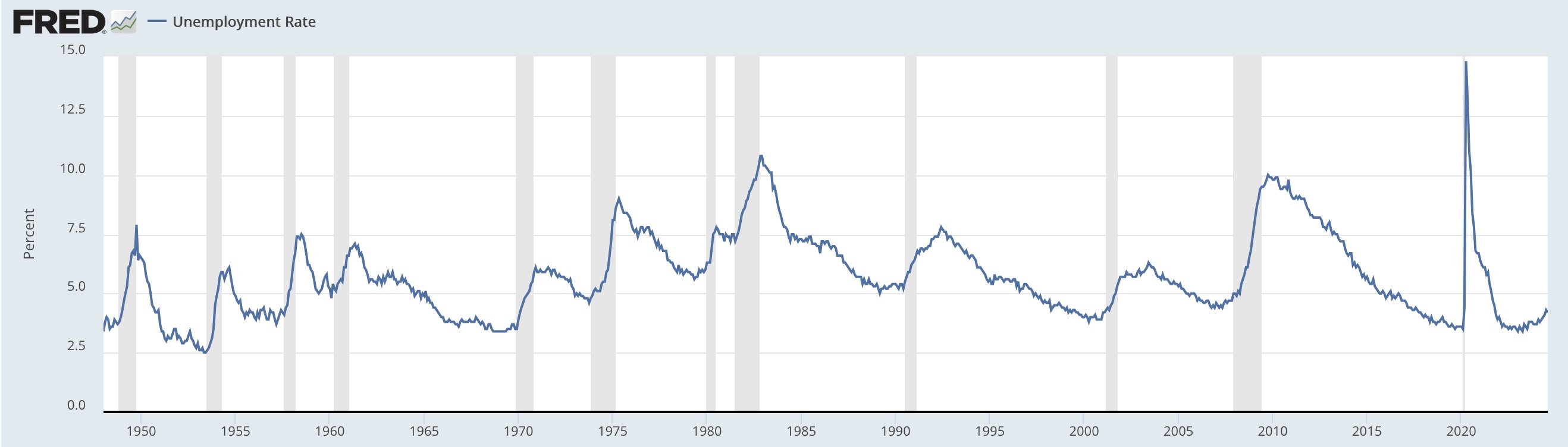

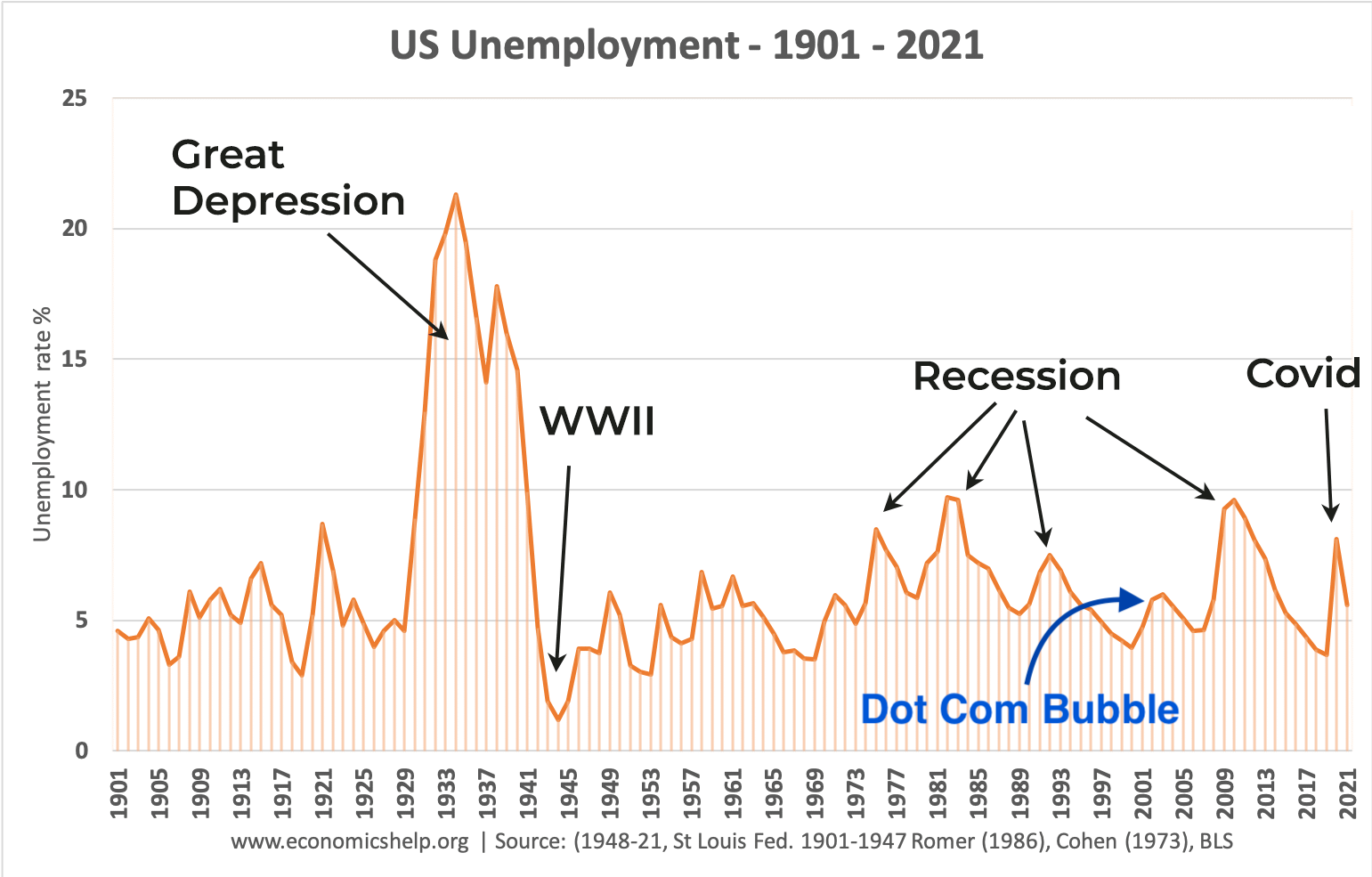

- On one hand, macroeconomic statistics claim we’re doing better than ever. The unemployment is about as low as it can be [1]:

We’re even seeing headlines like “The U.S. Economy Reaches Superstar Status”

-

On the other hand, people currently feel really bad about the economy. Theories range from vibes are wrong to “groceries are too expensive” to “people get their opinions from the news and they shouldn’t because the news is too negative”.

-

For tech workers specifically, the job market has been horrendous recently. Most explanations focus on interest rates. Gergely Orosz comapres the current situation to the dot com bubble, which I think is accurate.

There is no paradox

The narratives in the previous section aren’t a paradox. Specifically:

-

People get their economic opinions from tiktok and grocery prices. Consumer confidence is an aggregation of stupid opinions, not a sound macroeconomic assessment.

-

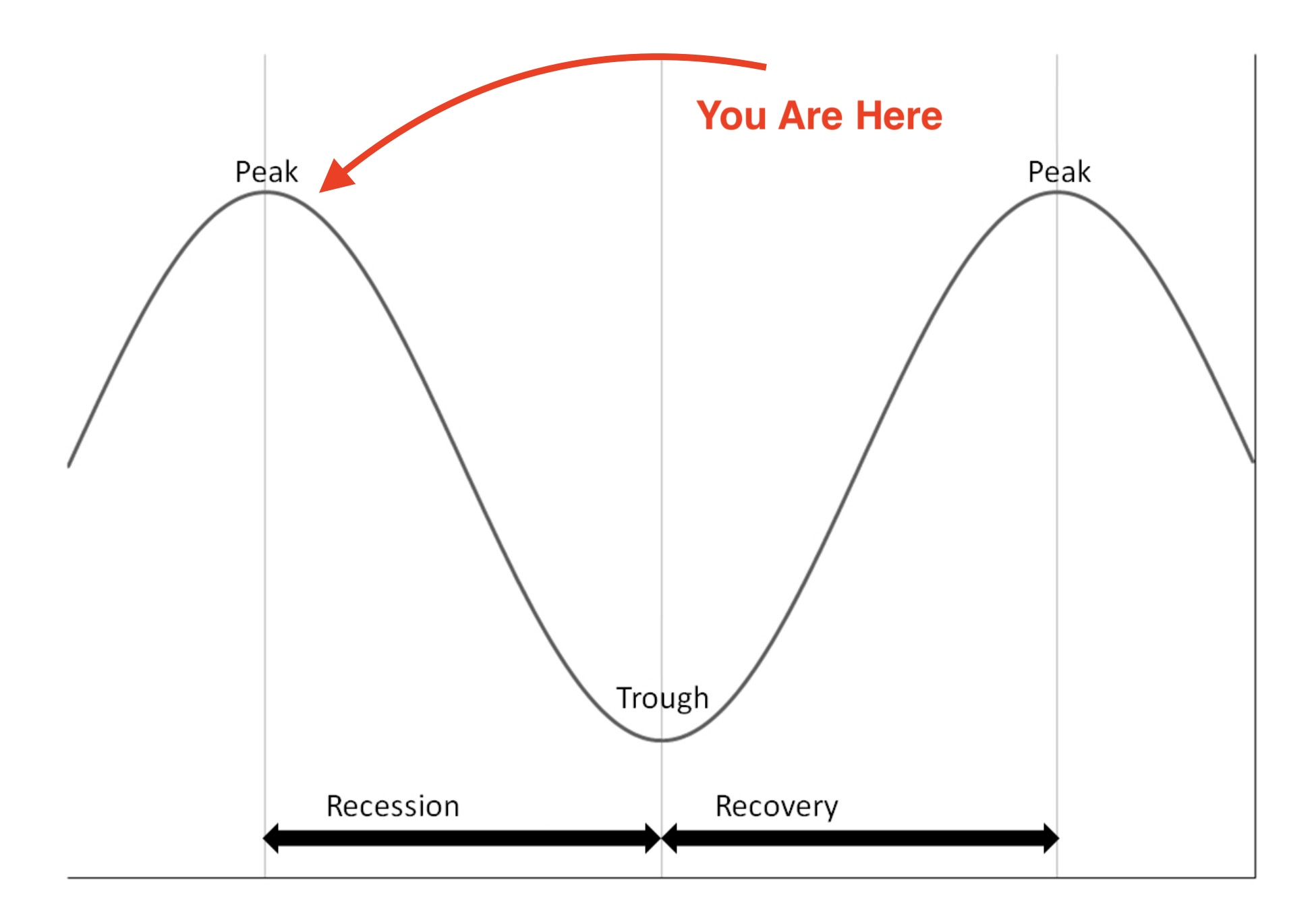

The economy is doing great because we’re at the top of the business cycle:

This is a logically easy statement: if the unemployment rate is at the lowest possible value, it can only worsen from here.

- Tech jobs are harder to come by because growth industries tend to drive market manias and get hit the hardest in downturns.

We were at market peak before COVID

The most common metric quantifying how out of touch with reality the markets are is the “PE” ratio. The PE is the ratio of the price of a company’s shares on the market to their earnings per share.

Very roughly, a PE of 10 says “the company needs to make profits for 10 years for you to break even on the investment”. Very high PE ratios indicate people think a company will grow a lot, or that there’s a market mania. The companies in the S&P 500 are currently sitting at a difficult-to-believe PE of 36:

Tech stocks are even worse - for instance, NVIDIA has a PE of 57 at time of writing even though it’s facing strong headwinds.

The market is terrible to invest in right now

Note: I’m using John Hussman’s research heavily in this section. I encourage readers to read his monthly newsletter for market analysis.

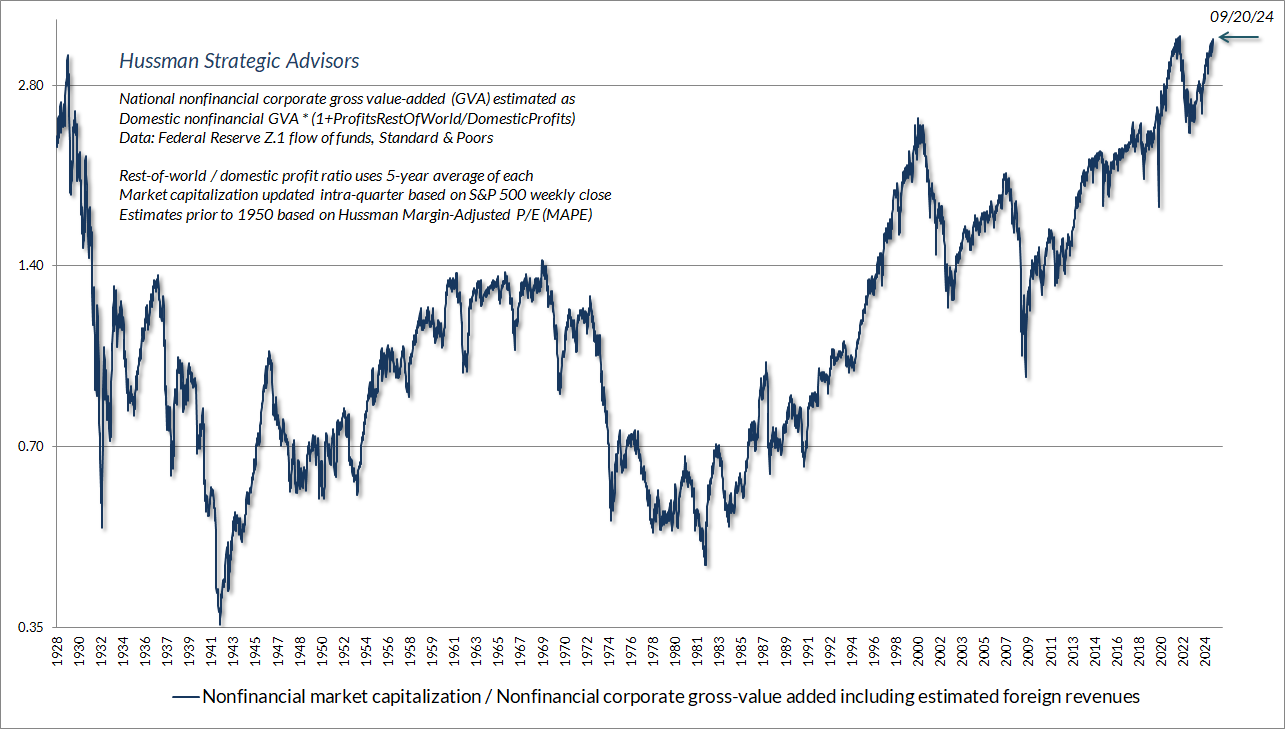

There are better measures than PE. John P. Hussman uses the ratio of Price to GVA (Gross Value Added) (PGVA), which gives a worrying picture:

What’s interesting about the PGVA metric is that it’s a very, very strong predictor of the returns in the stock market over the next 12 years.

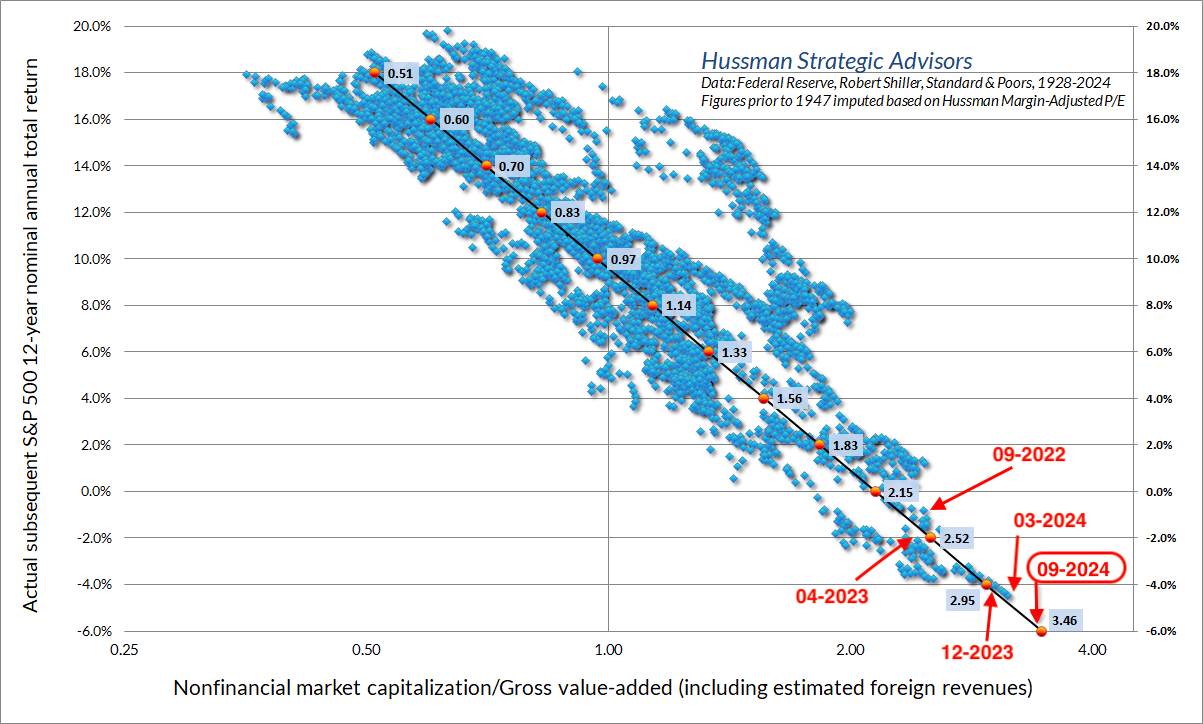

The following chart is hard to read. Just notice we’re currently sitting at the bottom right corner for now:

The chart is a simple linear regression of PGVA on the market returns of the S&P500 over the next 12 years. Each blue dot is a single month over the 1928-2024 dataset.

The X axis is the S&P 500’s PGVA ratio for that month in history.

The Y axis is the subsequent 12-year returns of the S&P 500 if you buy it on that specific month. Data points in the recent past are extrapolated from the model.

Notice that the simple regression fits the data very well. PGVA is a very strong predictor of the market over the next 12 years. We say that you can’t predict a market bubble - this may be true over a period of a few months, but predicting bubbles is actually easy over long time horizons.

Also notice that we’re sitting at the bottom right. Investing in the S&P 500 today would expect returns of -6% on average until 2036 based on this model.

Subscribe!

By the way, if you like my blog, you can subscribe by RSS or follor the mirror on substack:

For the love of god, please don’t try to short the SP500

I want to take a tangent to say: the point of this article is ABSOLUTELY NOT that you should short the stock market. Even if we were expecting a -6% return over 12 years.

Notice that unlike previous posts, there’s no disclaimer at the top of this article.

I have nothing at stake in the analysis here, I’m fully disinvested from the market right now.

Shorting is a bad idea at the best of times[2]. It’s throwing money away in all other cases. I would know, because I’m one of the few with direct experience on the matter. In fact, I’ve made my money from the exuberance of this economic cycle already.

My experience shorting the crypto bubble

Those following my blog remember that I was critical of the cryptocurrency mania in 2020-2022 and actively shorting cryptocurrency-related stocks.

Notably, I’ve collaborated with James Block, the prodigial cryptocurrency fraud investigator who exposed billion dollar Ponzi Schemes. I’ve worked with James on Signature Bank NY and Silvergate Bank’s underreported involvement in risky cryptocurrency schemes. I wrote a piece on the topic and shorted them around 6 months before they both went bankrupt.

I did well[3], but even in my lucky case, my short positions lost money for over a year before the Luna Ponzi Scheme exploded[4]. In almost any other case shorting loses money on expectation

I’m not exposed to the markets right now. I’ve since cashed out and used the proceeds to remodel a townhouse in Montreal:

I’ll have an article detailing why the common view of short sellers is misguided at some point, but for now, just don’t short. If you’re worried about a recession, put your assets in safe stuff.

Economic downturns aren’t all Great Depressions

But downturns do mean a winter in growth sectors.

When people think of speculative economic manias, they think of extreme cases where people pay tons of money for something of that has no economic value like tulips or cryptocurrencies.

The reality is that most bubbles are based around transformative technologies. People overestimate the short term economic impact of the new technology. This leads to a mania in valuations. Here’s a few historical examples:

-

The Dot-Com bubble overvalued internet technologies over a period of 3 years, but the internet did become a transformative technology. Even the poster child of speculative excess, Pets dot com would look very normal in 2024, where Chewy exists. Also, Pets dot com and beanie babies look positively sane compared to moviepass, GME and cryptocurrency manias.

-

Bubble historians remember the Railroad mania in the 1840s. It’s hard to understate how large of a shift trains were in humanity’s options for transporting things. Trains kept being useful after the bubble popped.

-

The 1720’s South Sea bubble also came from a place that made economic sense: colonial expansion and trading was novel and extremely profitable.

-

Similarly, LLM technology is obviously useful. It’s much more dubious how profitable it can be, however! We’ll learn that over the next 5 or so years.

Economic downturns are considered bad when they create huge unemployment, like in 1929 and 2008. The dot com bubble, on the other hand, didn’t:

The dot com bust made some VCs very sad. It made the tech job market bad. But, importantly, your plumber didn’t lose his house because of it. Moreover, tech jobs came back within 4-5 years.

So while it’s not impossible that this market cycle will be as bad as 2008, it’s also possible it will only wash out the growth sectors.

You should probably be more worried if your job is in mania driven sector. If resume’s last two line items are something like:

-

“Working on an app that layers something over the ChatGPT AI”

-

“Worked at a defunct crypto startup”

You should reconsider what you’ll be working on for the back half of the 2020’s. Also if options are part of your pay, maybe try to exercise or hedge them options ASAP.

You should be less worried if the thing you’re currently working on makes actual money, even if your job involves writing code all day.

Maybe companies should be profitable

The zero-interest rate environment of the 2010’s distorted the view of what startups should look like. Making negative profits for each sale was considered OK as long as the number of users or sales kept growing. Here’s some fun examples:

-

Moviepass was the epitomy of “negative unit profits driving growth”. The business model can be simplified as “selling a $1 for $0.95”. This will lead to a lot of people jumping onto the service! But you’ll also go bankrupt eventually.

-

WeWork’s play was to convince investors that subleasing office space is the same thing financially as making a tech startup. The investors happily bit the hook: subleasing is boring, but subleasing while promising fantasy profits is great! The investors also looked over a bunch of self-dealing from the CEO Adam Neumann that frankly looks like a legal form of embezzlement.

-

Twitter has managed to have 8 profitable quarters in its entire 18 year history.

-

Uber has had 5 profitable quarters in 15 years

How Market Manias are constructed

Both RYXCommaR and Gergely Orlosz note that interest rates have to do with the current tech job market being difficult.

This is correct, but getting from “interest rates” to “I can’t find a job” is a leap in logic that merits explanation[5].

-

VCs need investors. VC’s aren’t just billionaires like Peter Thiel dumping money into companies they like. VCs are an intermediary that let investors put money into startups.

-

When interest rates are low or zero, investors have bad returns on traditional, low-risk investments. Bonds and low risk debt vehicles pay close to nothing, because the interest rates are zero.

-

When interest rates are low, when calculating the returns to an investment, future profits are at a discount. Debt is cheap: easier to finance an investment on debt, and holding the investment over longer periods of time is cheap.

-

If the future is cheap, existing profitable companies are less attractive than possibly more profitable ones in the future. This also means that existing profitable companies will start focusing on dubiously profitable projects (eg. shoving expensive chatbots into anything) because it boosts the stock price.

-

Number 4 above leads to manias.

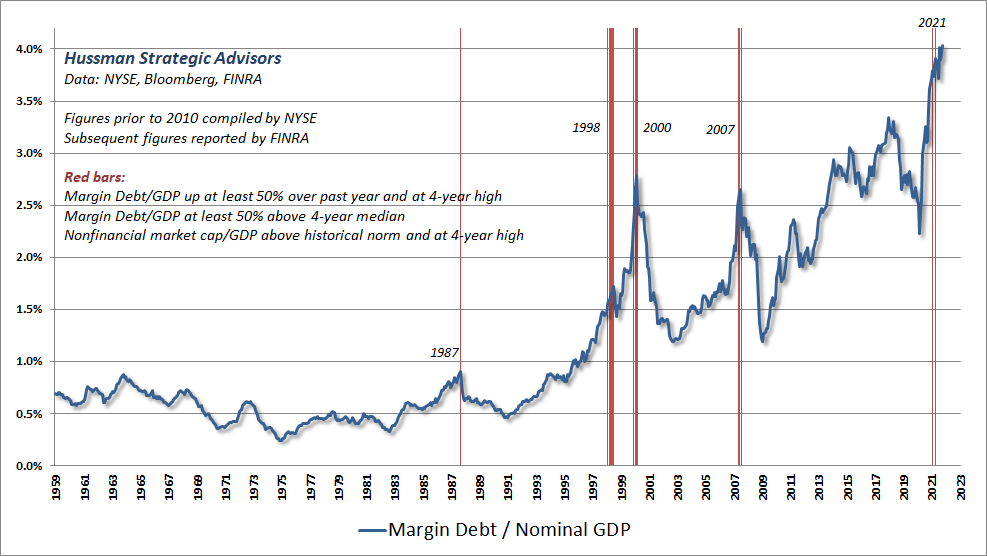

The market has been fueled by incredible amounts of cheap debt over the last 10 years:

The fact that anything making vague promises of future return eventually was profitable to invest in for a decade eventually creates an inability to differentiate good ideas from bad ones. That manic indifferentiation of ideas can grow to full blown delusional behavior (see: Moviepass, Gamestop, crypto) when taken to extremes.

The subsequent market downturn is supposed to regulate the mania: bad ideas need to lose money. Manic investors in meme stocks and financially dubious AI startups won’t change their opinion on the investment until there’s actual consequences to the bad decision.

Pessimists are always early

It’s easy to call a bubble. They’re pretty obvious, to be honest. It’s hard to time them, and to gauge how deep the following recession will be.

Note that smart skeptics will generally be early to call bubbles, often by years. I was too early by 18 months on the cryptocurrency bubble. The bubble even came back since then! Even the previously quoted John Hussman has called the market conditions dangerous for over 3 years now.

There are signs that the bubble is deflating right now - noted bubble historian Jeremy Grantham notes a lot of ongoing patterns we’re that note we’re past the peak.

Subscribe!

By the way, if you like my blog, you can subscribe by RSS or follor the mirror on substack:

The floor on unemployment rate is not 0%, because there’s normally a time gap when you switch from one job to another. This true floor is called the “natural rate of unemployment” and is generally estimated at 4-5% for the US. ↩︎

The only really good time to short something is when it’s a fraud that will imminently collapse to $0. You don’t want to hold short positions for long times, and you don’t want to expose yourself to the risks of short positions and the leverage they require unless the possible gain is massive. ↩︎

My tax returns say I’ve made ~$38k over 2020-2022 shorting crypto, for a 8x total return. ↩︎

The technical part of why this worked out so well for me specifically was that the options market for put options on Signature Bank NY were hilariously underpriced at the time I wrote the article. SBNY’s options were priced like it was as risky as a bank, with implied volatilies in the 40-55% range. Other stocks exposed to cryptocurrency risks were in the 100%-200% range. This meant you could get a position with unnaturaly cheap leverage shorting SBNY at the time. ↩︎

Note: the fed doesn’t care about your portfolio returns Investors crying about the central bank’s interest rate decisions are about as reliable as conservatives crying that a new policy will lead to full communism. The central bank cares about inflation being around 2% and unemployment being around the natural rate. It does not care about your portfolio returns, and only cares about banks insofar that banking crises can affect the unemployment rate or inflation. ↩︎